“Significant additional workload” – How the Self-Determination Act is pushing Berlin’s district offices to their limits

The Self-Determination Act is intended to create freedom. But the practice in Berlin's district offices shows that the state is shifting responsibility onto overburdened administrations.

With the entry into force of the Self-Determination Act, politicians promised a turning point in the way gender identity is addressed. Psychological tests and assessments have been a thing of the past since November 1, 2024. Since then, an appointment at the registry office has been sufficient to change one's gender registration and first name. The aim of the amendment was to reduce bureaucratic hurdles for transgender, intersex, and non-binary people. The motto is: freedom instead of justification.

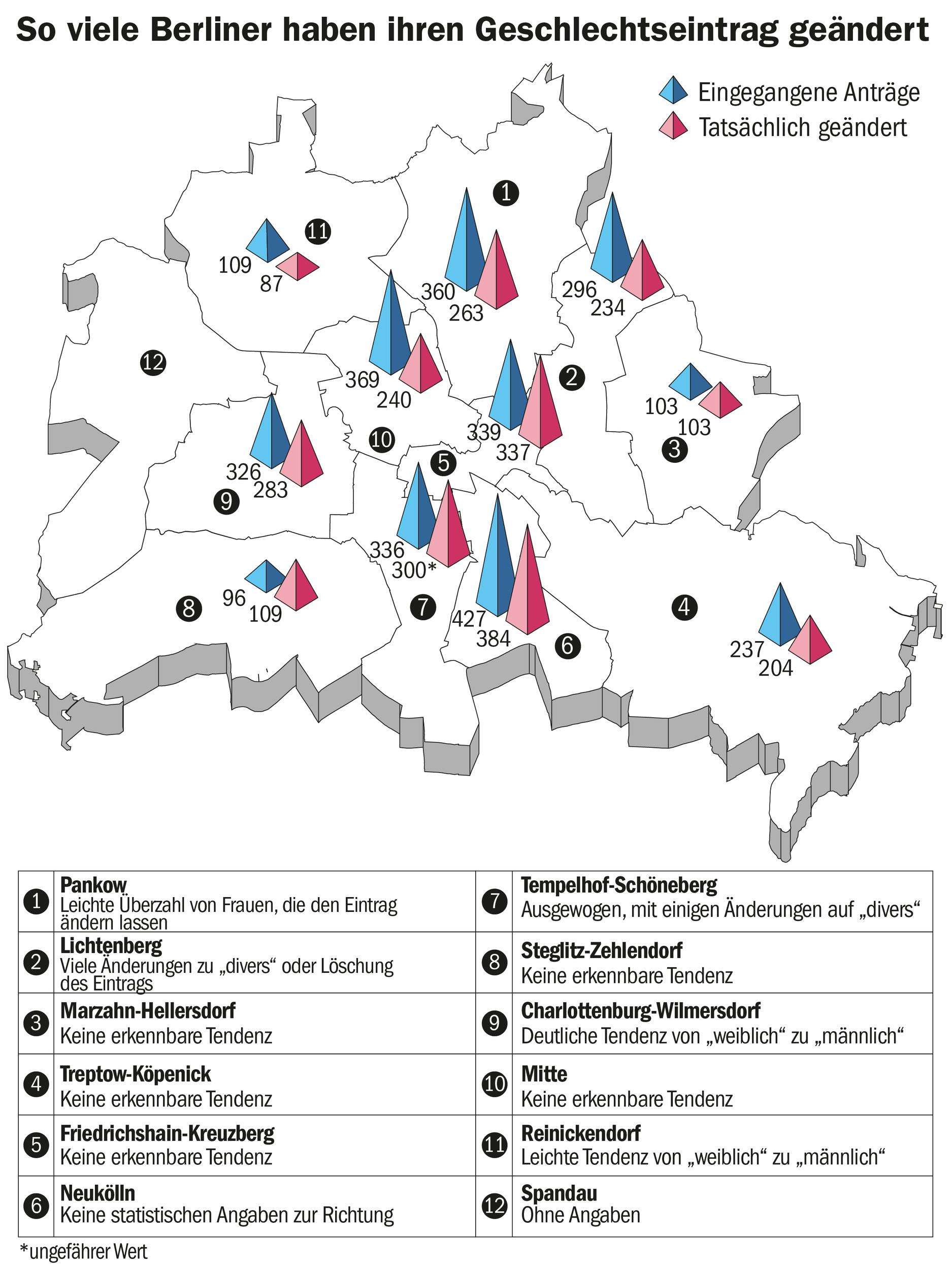

In practice, however, the freedom of one also means considerable additional work for the other, in this case: the responsible authorities. After almost a year, Berlin's district offices are drawing a sobering conclusion. Eleven of twelve district offices provided information to the Berliner Zeitung – on figures, gender-specific trends, and changing processes. Their answers raise a fundamental question: Does the Self-Determination Act truly create order, or does it simply create new construction sites without tools for the already overwhelmed offices?

Almost a year ago, activists and supporters of the queer community gathered at the Brandenburg Gate. Not to demonstrate, but to celebrate. The "Law on Self-Determination with Respect to Gender Registration" (SBGG) was no longer a hotly debated idea. On this day, in early November 2024, the previous Transsexual Act (TSG) from 1981 was replaced by the Self-Determination Act. An "outdated" law that was perceived by parts of the queer community as disempowering and humiliating.

Critical voices warning of an increase in assaults in so-called safe spaces—changing rooms, women's shelters, saunas—have since fallen silent or are barely audible. Since then, all Berlin registry offices have maintained a new list: that of name and gender changes. A first glance at the figures presented to the Berliner Zeitung by all district offices, with the exception of Spandau, is clear: the law is being used. And actively.

The number of applications for gender reassignment is in the triple digits in almost all boroughs. Particularly high numbers were reported in Neukölln with 427 applications, Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg with 339, Tempelhof-Schöneberg with 336, Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf with 326, and Pankow with around 360 applications. Fewer applications were recorded in Treptow-Köpenick (237) and Reinickendorf (109). The proportion of changes actually carried out varies between 80 and 90 percent, depending on the status of the procedure.

When it comes to the distribution of applications for specific gender reassignments, there is no consistent picture. In most districts, no distinction is made between male and female, but rather between binary and non-binary.

The latter refers to all those who identify neither clearly as male nor female, or who consciously reject these categories. Nonbinary is not a clearly defined "third gender," but rather an umbrella term for diverse identities. Some consider themselves genderfluid, meaning they fluctuate in their gender identity. Others describe themselves as agender—without affiliation with a gender. This also includes those who identify between the genders or use their own terms.

The Self-Determination Act takes this development into account, for example, by allowing individuals to delete their gender entry or to register as "diverse." In contrast, the binary model is based on the classic division into "male" and "female." Transgender people who, for example, transition from female to male or vice versa can also identify as binary if they clearly identify as belonging to one of these two genders.

The gender change from female to male predominatesOne notable feature, however, is that the proportion of women changing their gender entry to "male" predominates. In Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, there is a "clearly discernible trend" toward more applications being made from female to male. In Tempelhof-Schöneberg, two-thirds of the declarations related to binary changes, one-third to "diverse" or deletion of the entry.

Reinickendorf reports 40 changes from female to male, 25 from male to female, along with further declarations of "diverse" or no entry. At the Lichtenberg registry office, the number of people who have changed their gender entry to "diverse" or requested its deletion is 107 – significantly above the average compared to other districts.

Questions about name selection and possible rejections are answered with a resounding "no" by almost all districts. Extreme cases like those in Hesse, where applications were made for the first names "Pudding" or "Diamond Caramel," do not occur in Berlin. The Neukölln district office explains the smooth name change process by the fact that consultations were held in advance: "Therefore, all first names were approved." Only Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf speaks vaguely of "some procedures being clarified." Details are not provided. Almost unanimously, the districts report a significant increase in workload. This is not because the procedures are technically complicated, but because of the accompanying circumstances: consultations, software deficiencies, deadline monitoring, and ambiguities. The Tempelhof-Schöneberg district office lists the additional tasks: "Advice on the procedure by telephone, in person on site, or by email, processing the application for appointment scheduling, internal collegial consultation on ambiguous cases, research on the desired first names, and notifications to other authorities."

Particularly problematic is that many software systems, such as the specialized AutiSta procedure, are not usable for the new procedures. Therefore, in Reinickendorf, everything has to be "recorded manually and printed out on paper."

New departments were created despite staff shortagesThe Treptow-Köpenick district office also reports that the legally required three-month deadline has increased the burden on staff. In Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, there is talk of an "increased need for coordination" among employees. The Mitte district office articulates one reason for the need for intensive consultation: "The interpretation guidelines of the federal ministries involved first had to be aligned with practical cases."

The handling of the Self-Determination Act varies from borough to borough. In Neukölln, despite a staff shortage, intensive preparations for the changeover have been made: "An additional department has been established at the registry office to deal specifically with 'special certifications.' However, no additional positions have been created for this purpose." In Steglitz-Zehlendorf, the new service "led to longer processing times for other services," while in Pankow, the additional workload is "significant compared to other name declarations."

As clearly formulated as the law is for applicants, many ambiguities remain in day-to-day administrative processes. A central problem is structural: the lack of digitalization. Many procedures are or must be carried out on paper, even though the law was only introduced last year. The reason: the "appropriate software" is missing.

What will happen now? Will everything remain as before despite increasing pressure? At present, these questions are only partially answerable. A comprehensive evaluation of the Self-Determination Act is still pending. The coalition agreement between the red-black federal government provides for an initial evaluation by July 31, 2026. Among other things, the evaluation will examine the impact on children and young people, the appropriateness of the time limits, and the protection of women in sensitive areas. Furthermore, the law itself requires a further evaluation by the end of 2029 at the latest. The focus is on the question of whether the process is simple, unbureaucratic, and practical.

The Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, upon request, stated that the Federal Government cannot currently quantify how many people have made use of the new Self-Determination Act so far. It is currently assumed that the number of applications nationwide annually estimated in the explanatory memorandum to the law is realistic. This estimate, given the current figures from Berlin's district offices, appears to be significantly underestimated. Despite all the uncertainty that still exists after a year of the amendment, at least one thing is certain: its implementation reveals a long-standing problem. Municipal administration is left to its own devices: without sufficient staff, without digital infrastructure, without central coordination. The consequences: significant additional workload, unclear procedures, and a lack of information. The registry offices are responding pragmatically, committedly, and professionally. But their efforts alone will not be enough in the long run. If self-determination is politically desired, the administrative conditions for it must also be created. Otherwise, the freedom of one person will come at the expense of a system that is already on the verge of collapse.

(All figures and quotes are taken from responses by Berlin district offices to a written inquiry from the Berliner Zeitung, as of July 2025.)

Berliner-zeitung